This feature is part of a series focused exclusively on cybersecurity. To view other posts in the series, check out the spotlight page.

There is something visceral about responding in kind. When attacked, instinct says to lash back and defend, counteracting a threat.

In cybersecurity, the retaliatory counterattack is better left to the nation state actors, the intelligence agencies tasked with identifying and neutralizing threats the private sector faces.

If a company is hacked, it is left few options, save for quickly acting to defend. Retribution, however, is best left to experts.

But why can't companies fight back, taking revenge on those who target their networks, debilitating them while they're at it?

- One of the main reasons is it's illegal to launch a cyberattack. Though the laws can sometimes be left subject to interpretation, under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act it is illegal to knowingly access a computer without authorization. Some states have made specific crimes illegal to allow for harsher punishments. In California, for example, it is now a felony to use ransomware.

- Some experts fear that a company launching a retaliatory cyberattack could escalate an incident, leading to a War Games-like scenario.

- There is also a lack of resources. The average company does not staff a roster of hackers dedicated to targeting other organizations.

"For the most part, it's illegal to mount a cyberattack and there's a lot of liability attached to it, especially if you're wrong," said Dimitri Sirota, CEO of BigID. "The other thing is, are you going to provoke an even bigger reaction?"

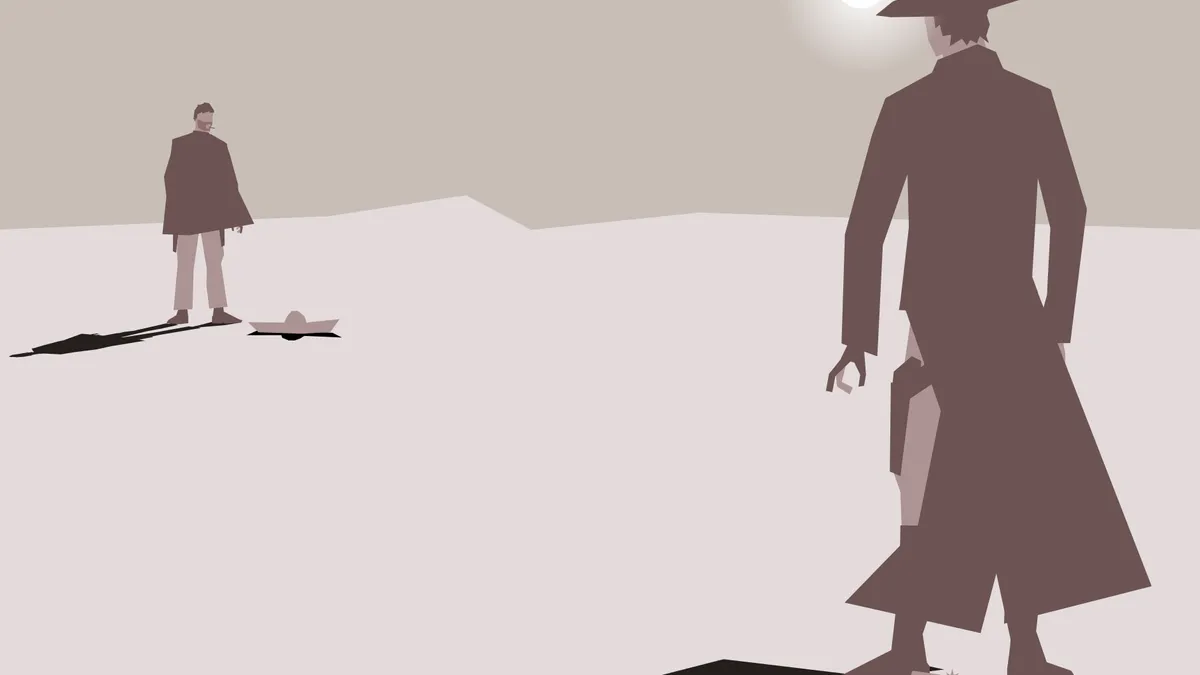

Though the internet can be wrought with threats, targeting companies of any size, that's not to say it's the Wild West. There are still best practices and rules in place that dictate what a company legally can and cannot do in terms of cybersecurity and threat response.

"For the most part, it's illegal to mount a cyberattack and there's a lot of liability attached to it, especially if you're wrong. The other thing is, are you going to provoke an even bigger reaction?"

Dimitri Sirota

CEO of BigID

The average company doesn't necessarily have the resources of an intelligence organization or the ability to accurately locate an attacker. There are also potential legal repercussions and liability associated with hacking back.

"You have a right to protect what is yours and you actually have an obligation to protect your partners that are connected to your network," said Doug Saylors, director at ISG. "But once [you] cross the line and start trying to break into other environments, at that point you are effectively breaking the law."

How to 'attack'

Companies are not without their capabilities. Though companies aren't legally going to launch a cyberattack against an aggressor, they can still actively defend themselves from attack, whether from a DDoS attack or the threat of a hacked server. The more active, or offensive, form of attack, plays into any companies available defensive strategy.

"Cybersecurity has reached an element that in a very quick period of time, somebody can put a hurt on your organization that you can no longer recover from," said Carl Herberger, vice president of security solutions at Radware. In the event of an attack, companies cannot just wait for assistance, hoping their security tools hold. Instead, they must defend themselves to guarantee that a cyberattack doesn't get worse.

Defense tactics can take either a passive or active approach, according to Herberger. Passive techniques are focused on neutralizing an attack, making an onslaught ineffective. Or they can center around deception technology, presenting so many targets that attackers are under-resourced and cannot identify the authentic target.

"Cybersecurity has reached an element that in a very quick period of time, somebody can put a hurt on your organization that you can no longer recover from."

Carl Herberger

Vice president of security solutions at Radware

"The idea is that you make something in your network look so attractive that it becomes the focus for the attacker," Sirota said. Companies even create entirely fake servers to confuse an attacker.

Active techniques, however, are where most people start to have objections, though they can be valuable, according to Herberger. Whether it's a DDoS attack, SQL injections or a brute force attack, those techniques can also be available to an attacked company.

Active techniques center around companies taking action during the first disrupted session, not waiting for attackers to continue their attack. Organizations can identify an attackers application as a potential problem and "proactively make sure that application doesn't work," Herberger said.

Why not take revenge?

If a company's servers are breached, or its networks are taken down by a large-scale DDoS attack, some may want to seek revenge and mount a cyberattack. So why don't they?

"Few organizations have the resources of an FBI or a CIA and so there's a high degree of risk," said Sirota.

And even if a company did attack, there is the potential to solicit an even bigger reaction. Back and forth attacking isn't necessarily in the purview of the average corporation. Depending where your company is located, there are also potential legal repercussions and liabilities associated with an attack.

"Once you take the next step and actively break into the systems, that's where it becomes an issue. I don't think companies really want to be in the business of breaking into other company's systems."

Doug Saylors

Director at ISG

Revenge is best left to the nation state professionals who can work to identify the origins of attacks and take legal action if necessary. But more often than not, attackers can remain anonymous on the internet, not held responsible for criminal activity.

Though a company cannot easily respond to an attacker, that's not to say they can't be prepared.

"I don't believe it's actually illegal anywhere to scan someone's network or find information you can find," Saylors said. "But once you take the next step and actively break into the systems, that's where it becomes an issue. I don't think companies really want to be in the business of breaking into other company's systems."