The Federal Communication Commission (FCC) dished out $9.2 billion this December to help companies close the digital divide for an estimated 10 million people in rural areas.

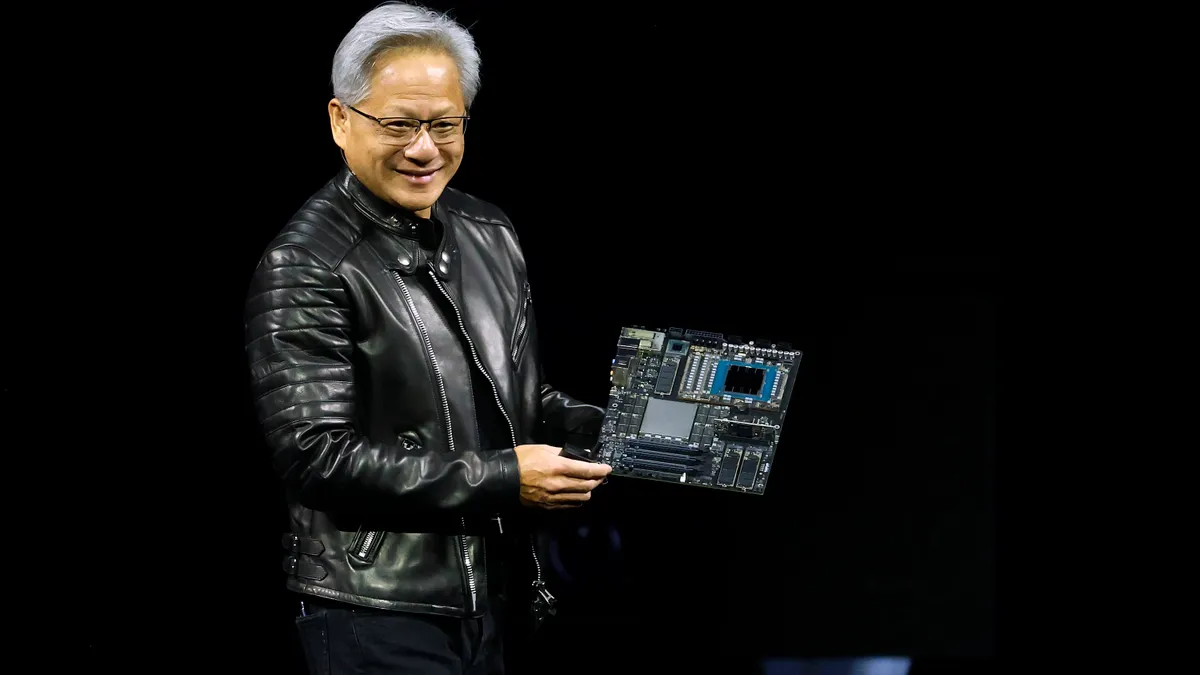

Elon Musk's SpaceX was one of the biggest recipients of that Rural Digital Opportunity Fund (RDOF), receiving a controversial $885.51 million for its Starlink service, which uses low earth orbit (LEO) satellites to provide internet access.

The backlash for that decision was swift, triggering a firestorm of criticism against both the FCC and satellite internet technology. Opponents and industry experts expressed concerns about Starlink's cost and ability to live up to SpaceX’s big promises. Despite the skepticism the technology faces, it still holds the potential to curb a digital divide that has plagued rural parts of the country for years.

"The novelty here is positioning networks of scale and having them service potentially millions of consumers," said Tyler Cooper, editor-in-chief at internet comparison and research firm BroadbandNow. "That part is, I wouldn't go so far as to say it's unproven, but it's certainly something that we haven't seen deployed at the scale that SpaceX would like to do."

Amazon and SpaceX hedge their bets

SpaceX has outlined lofty goals for its Starlink program. The company said it hopes to deploy as many as 42,000 LEO satellites, with 1,000 already deployed as of January. Using its rockets, SpaceX says it can deploy up to 60 satellites at a time.

In a regulatory filing with the FCC, SpaceX said the technology can deliver speeds of more than 100 megabits per second (Mbps), including in rural areas that traditionally have been underserved by internet companies. That speed can handle common uses for up to five users at a time.

SpaceX is not the only company looking at LEO satellites to provide internet access, though. Amazon also has thrown its hat in the ring through its Project Kuiper initiative, receiving permission to deploy 3,236 satellites and pledging to inject over $10 billion into its network.

Customers would receive an antenna, satellite dish or other receiver for their home. Using radio waves, those devices would communicate with satellites orbiting in space, connecting the satellite signal to the home's modem. With satellites in higher orbit, that transfer of data can sometimes lag; LEO satellites eliminate much of that delay.

The satellites communicate with each other and share the connection loads as they orbit, creating a mesh network that provides customers with more stable internet service.

"In a perfect world, we would just push for universal fiber adoption, and it would be great. Unfortunately, that is unrealistic."

Tyler Cooper

Editor-in-chief, BroadbandNow

A viable option for rural areas

People in rural areas stand to benefit the most from satellite internet, according to analysts, especially as existing providers have been unable to make a business case for connecting households with fiber.

"In a perfect world, we would just push for universal fiber adoption, and it would be great," Cooper said. "Unfortunately, that is unrealistic, especially for somewhere like America, where we have massive differences in population density and wide-ranging topography. Fiber is incredibly expensive to build out, especially in rural communities, because we're talking about return on your investment."

The technology has also come into greater focus during the coronavirus pandemic, which has highlighted the yawning digital divide. Unlike fiber, satellite technology has become a much more viable option as technology has advanced and the service has become more reliable than in the past, when inclement weather could affect satellite connections.

"We're seeing a more robust satellite service that is actually able to cut through weather and clouds," said Ryan Johnston, policy counsel for federal programs at advocacy group Next Century Cities. "Back when satellite was first starting, a lot of times, if it was a cloudy day, you wouldn't be able to receive service. But now, we're seeing with satellite service in the higher spectrum bands, it's much easier to punch through those clouds."

Skepticism of the technology and its costs

Despite satellite internet's potential, many concerns remain about the technology and the FCC's decision to award SpaceX money to provide service in 35 states. A major stumbling block for internet equity advocates is the cost of service, which could be a barrier for many potential customers.

SpaceX's Starlink service costs customers an initial $499 to get online, and then it's priced at $99 a month under its beta test. Johnston said that cost could be prohibitive for rural Americans. Amazon says its custom-built antenna for Project Kuiper can allow the company to "deliver a small, affordable customer terminal."

"A lot of the people that use this are low-income rural Americans," Johnston said. "And if we're saying it's $100 a month for you to get service, that could be the difference between them paying a broadband bill or paying for groceries that month. To say this is the only option that you have is a significant problem."

Not all experts agree about the cost concerns, however. BroadbandNow said if Starlink and Project Kuiper deliver on their promises, adding LEO satellite internet into the mix could save Americans more than $30 billion by improving competition and driving down prices.

Major skepticism also still surrounds the technology itself, though, as many experts have derided it as "unproven." Opponents raised concerns during a virtual press conference hosted in February by the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association (NRECA), which represents groups also involved in rural broadband deployment and sent written comments to the FCC.

"We're using the public's money in the RDOF auction, and it's designed to be a deployment program for proven technologies, not a research and development experiment for technologies that may not be capable of connecting Americans with real broadband," NRECA CEO Jim Matheson said during the press conference.

Those on the media call said LEO satellites provide unreliable service and questioned whether connections would be as fast as promised. Tim Bryan, CEO of the National Rural Telecommunications Cooperative (NRTC), questioned if the satellite network and spectrum will be robust enough to handle the expected number of users.

"My concern is mostly around the capacity, not of one or two users, but what happens when you get to 20, 30, 40 or 50,000 users, because obviously you have to share the same constellation across the entire country," Bryan said during the NRECA press conference.

A SpaceX spokesperson declined to comment on those criticisms. Instead, the spokesperson pointed to recent social media posts praising Starlink service, including one from the Washington Emergency Management Division noting its use in providing internet for a town rebuilding after wildfires, and another from the Hoh Tribe, also in Washington.

Happy to have the support of @SpaceX’s Starlink internet as emergency responders look to help residents rebuild the town of Malden, WA that was overcome by wildfires earlier this month. #wawildfire pic.twitter.com/xUSQOjcT4T

WA Emergency Management (@waEMD) September 28, 2020

Given that SpaceX is still looking to finish its proof of concept, though, Johnston said the FCC made a hasty decision in allocating its funds to the company.

"While this money absolutely needed to be put out into the world, I think the FCC was a little too quick to give it to a satellite provider," he said. "The way that SpaceX had marketed their product is fairly untested. The way that they're looking at it is in a very limited scope."

FCC spokesperson Anne Veigle rejected criticisms of its RDOF auction process, saying the commission "adopted a technologically neutral approach that allowed companies to use different technologies to bring broadband to unserved areas."

Veigle noted the next phase of the program requires all winning bidders to submit a long-form application where they outline their plans to provide service. "No funds will be disbursed until the Commission determines that a long form application is complete and meets all program requirements," she said in an email.

Not a silver bullet

As for now, it remains to be seen if satellite internet can help close the digital divide. Indeed, the FCC said in a recent report on internet availability that "data could overstate the availability of satellite services."

"While satellite signal coverage may enable operators to offer services to wide swaths of the country, overall satellite capacity may limit the number of consumers that can actually subscribe to satellite service at any one time," it continued.

There are also concerns about false promises made in the past to bridge the digital divide. The FCC awarded $789 million in 2015 to CenturyLink and Frontier to expand broadband to rural America. But both companies announced recently that they missed their deployment deadlines, a development Matheson called "troubling."

For local governments, there could be an opportunity to partner with satellite companies on base stations and other infrastructure on the ground. But Jane Coffin, senior vice president of Internet Growth at advocacy group the Internet Society, said the only way to get good internet is to foster competition, and for local communities to invest in their own networks.

A survey from the Broadband Equity Partnership echoed that sentiment, with 70% of the more than 120 respondents in 18 states saying that local economic development agencies can play a key role in encouraging locally owned networks and infrastructure, rather than relying on large companies when it may not be financially viable for them to do so.

"It can't just be the incumbents," Coffin said. "Small, medium and large size networks need to have availability, to interconnect to make sure their networks can take the traffic from one point to another… With some small community networks, they could backhaul out to a satellite or take their traffic, their connectivity, or emails from that base station up to satellite and have it transmitted in seconds to another satellite down to another country."

"I don't think there's any one technology that's going to be able to solve the digital divide because this is such a problem that has so many facets."

Ryan Johnston

Policy Counsel for Federal Programs, Next Century Cities

Next Century Cities Executive Director Francella Ochillo said the aim of having every household reach speeds of 25 Mbps is a noble one, as it is defined by the FCC as the base speed for broadband, but it is not forward-thinking enough given how important the internet has become. With internet of things devices set to multiply in the coming years, she said that will put more strain on networks.

"It's really important that we're constantly forward thinking, we're always looking for ways to be able to get people connected, but to get people to connect at speeds we're going to need tomorrow," Ochillo said. "We need to be thinking about what is the realistic speed that we're going to need five and 10 years from now."

Experts also warned it will take more than deploying new technology like LEO satellites to address the country's digital divide. The FCC estimated last year that just under 18 million people lack broadband, although broadband mapping has been criticized as not showing the full extent of the digital divide.

Estimates vary on how much it would cost to get everyone connected to broadband internet. When House Democrats reintroduced the Leading Infrastructure for Tomorrow's America Act (LIFT America Act), they pledged to invest almost $94 billion to reduce the digital divide.

Johnston said it will take a holistic approach that focuses not just on introducing new solutions, but also on helping teach people the skills they need to take full advantage of them.

"I don't think there's any one technology that's going to be able to solve the digital divide because this is such a problem that has so many facets," he said. "There's accessibility issues, there's affordability issues, we have digital literacy issues. So even if we are able to put the best satellite service out there that connects everybody in the country, we still have all these other issues that we need to address before we can say the digital divide has been closed."