In early November, a companywide walkout at Google saw an announced total of "nearly 17,000" workers across the globe protest for changes to company arbitration policies and pay equity, among other things. Some have formally organized under a single entity, Google Walkout for Real Change, which maintains an active presence on both Twitter and blog platform Medium.

Nearly a month after the walkout, members of the group's TVCs — short for temporary, vendor and contract workers — published an open letter to Google CEO Sundar Pichai in which they asserted the company denies them access to critical communication and treats them unfairly.

The TVCs referred to themselves as Google's "shadow workforce" and alleged the company did not provide them certain real-time updates during the April shooting at the headquarters of Google subsidiary YouTube.

The group also said Google did not include them in a company-wide town hall that followed the shooting, and it added that TVCs were similarly excluded from a company-wide discussion that occurred after the Google Walkout.

"The exclusion of TVCs from important communications and fair treatment is part of a system of institutional racism, sexism, and discrimination," the letter said. "TVCs are disproportionately people from marginalized groups who are treated as less deserving of compensation, opportunities, workplace protections, and respect."

Google has denied the substance of the letter. In a statement emailed to HR Dive, a Google spokesperson called TVCs "an important part of our extended workforce." According to a Google spokeswoman, the company did send updates to employees, but it had to send those notices through a different email address or through employers of TVCs in some instances.

Regardless of the back-and-forth, Google's TVC saga has reignited a long-running debate in the tech industry. And while one expert who spoke with HR Dive said Google's use of these workers probably isn't violating U.S. labor laws, the incident poses challenges for employers recruiting in an age of rapid technological change.

Contingent workers: A growing presence

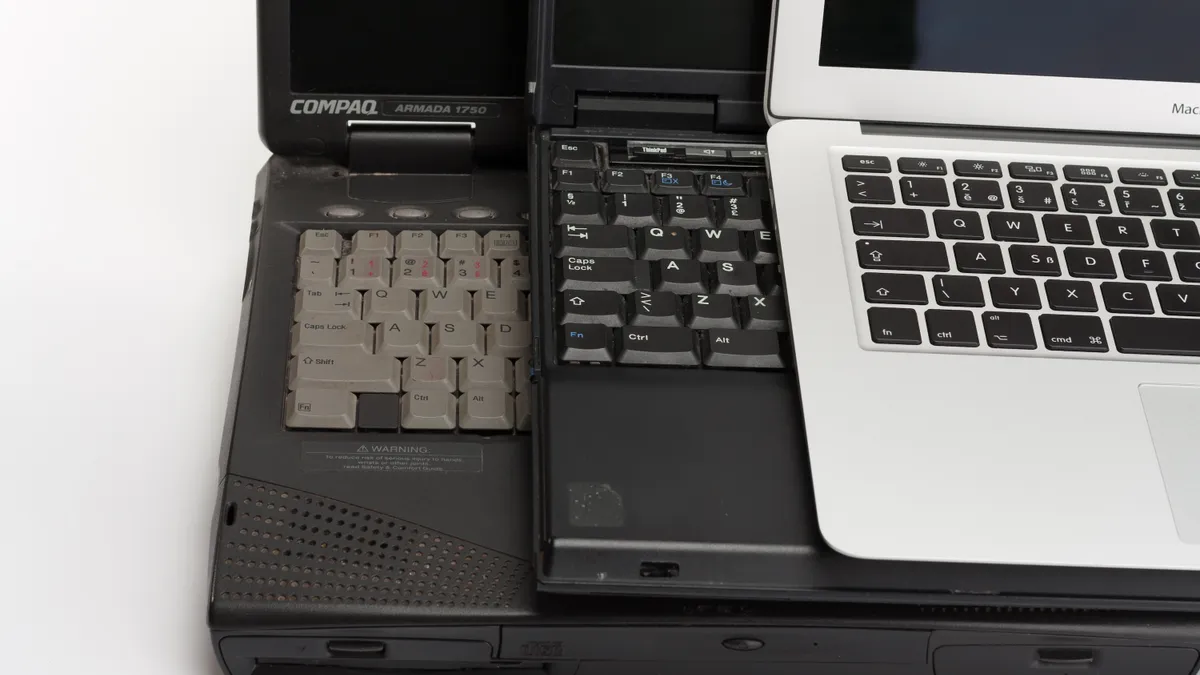

The so-called gig economy has evolved to encompass multiple forms of work, ranging from those who provide transportation services on apps like Uber and Postmates, to those who freelance or perform odd jobs through other platforms.

In turn, these forms of work can be grouped under the umbrella "non-traditional" work category that is sometimes used interchangeably with the terms "gig" and "contingent."

Authors of a 2018 Gallup paper determined that 36% of all U.S. workers have some form of "gig arrangement," be it their primary or secondary job, while 29% of workers hold an "alternative work arrangement" as their primary job. These numbers have followed an upward trend; for comparison, a 2005 U.S. Bureau of Statistics report showed 11% of U.S. workers had an alternative work arrangement as their primary job.

While that growth means TVCs are new to some industries, they aren't a new presence at places like Google.

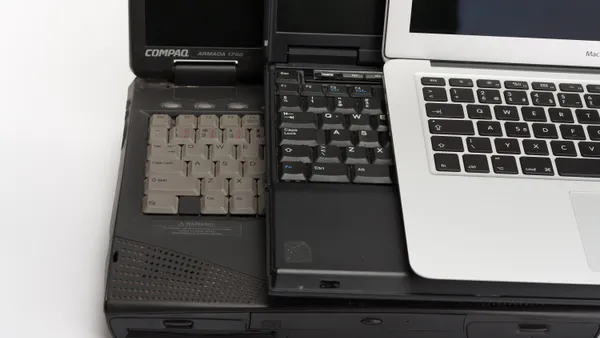

In fact, Google TVC complaints of "minimal benefits" mirror what happened at competitor Microsoft in the 1990s, when the company was sued by contractors over stock option benefits in Vizcaino v. Microsoft. That's the impression that Scott Absher, CEO of on-demand and gig worker platform ShiftPixy, had after reading the letter.

"I can see a similar dynamic here," Absher said. "You've got a lot of contractors who are working inside the hive there at Google that are not afforded some of the things that the [...] employees are, and they have expectations of such. I mean it's a very odd work environment. And this is the kind of thing that can happen."

But Absher believes this is typical of a tech industry that has become increasingly reliant on contingent workers, and the changing nature of that industry plays no small part in the dynamic. "They can't hire fast enough," he said. "They just can't move fast enough and this is what enables them to move faster."

That’s to say nothing of course of the enormous costs saved by hiring contingent workers. The average healthcare costs alone for a company of Google’s size hover in the range of $15,000 per worker annually.

Also, what distinguishes Google’s TVC situation is the sheer size of its contingent worker pool; reporting by The Guardian on Google's internal employment figures found that approximately 49.45% — about 170,000 persons total — of the company's global workforce is composed of TVCs.

Still, Absher said many TVCs prefer not to be tied down to one employer, preferring to work on projects that interest them. For some, there’s also appeal in the flexibility that non-traditional arrangements can provide.

A right to equal benefits?

Independence comes with a cost: contingent workers generally are not entitled to the benefits Googlers receive, like paid family leave, onsite massage services and access to financial planning resources. According to The Guardian's report, Google staff with TVCs on their teams aren't allowed to give them company T-shirts.

Instead, Google’s training documents instruct employees to send "a thank you a note," or "a note on G+," according to The Guardian.

Absher noted that while TVCs in many organizations are exempt from receiving even the most fringe category of perks due to liability concerns, Google's TVCs might still receive benefits like workers' compensation via a contracting firm that other contingent workers, namely those working for platforms like Uber, would not receive.

"So they're not in a deprived position like the Uber, GrubHub, DoorDash or any of those people that work in those environments are," Absher said. "They'd have that safety net in place."

It's clear Google Walkout's organizers feel differently. When contacted to comment for this story, the group directed HR Dive to a press release in which it equated the company's treatment of TVCs to one of many issues of systemic discrimination and marginalization. It also said TVCs tend to be "people of color, immigrants, and people from working class backgrounds."

"And [these issues] have the same root cause, which is a concentration of power and a lack of accountability at the top," organizer Stephanie Parker, a partner product specialist at YouTube and policy specialist at Google, wrote in the press release.

Some of these demands, however, could put Google at risk of running afoul of rules about how employers can interact with independent contractors. "While I understand their concerns, there's no legal basis for some of the things they're demanding," Absher said of the Google TVCs. Companies hew employment relationships in many cases so as to avoid joint-employer status, an area of employment law that is itself controversial, complicated and litigious.

Employers are generally advised by legal experts to establish strictly limited relationships with workers employed by third-party contractors.

Change could be on the horizon, however. The U.S. Department of Labor, under President Donald Trump, rescinded a strict Obama-era interpretation of joint employment. And the National Labor Relations Board recently proposed to relax its rules, specifically limiting joint employment to those workers over whom an employer exercises "substantial direct and immediate control."

Absher said Google TVCs may still theoretically have an argument in their favor, however. Courts in the Microsoft case did find that plaintiffs were due stock options. "And you could probably make that same argument here, that there is an upside to being an employee at Google, that these contractors who are helping to build in and help build Google's value should be entitled to participate in that way."

The dilemma for employers

Even outside of the benefits context, some of the TVC's demands could be met by Google, Absher said, particularly emergency notifications. "They should be either forcing that communication through the contractor, or loop everybody into it so they're mobilized as part of the Google population. If they're not an employee they're at least part of the population."

It isn't the only instance in which Google allegedly demonstrated poor communication. Just weeks after publication of the TVC letter, the Google Walkout Twitter account began circulating a series of #ContractWorkerStories tweets, featuring a story from one anonymous contract worker in which a manager forgot to renew their contract multiple times, leading to a week of lost wages.

#ContractWorkerStories Recently, my manager forgot to renew my contract. Just forgot. We spoke about it multiple times, and I'm still processing how this could ever happen. Now, I've lost a full week's wages, right after coming back from 2 weeks off that was planned a year... pic.twitter.com/mDpTJ4QaK1

— Google Walkout For Real Change (@GoogleWalkout) December 18, 2018

A Google spokesperson did not respond to the tweet specifically when presented it in an email query from HR Dive.

Google's policy, according to a company statement, is to draw a distinct line between employees and non-employees.

In a statement provided to Retail Dive, the company said, "Our Supplier Code of Conduct holds companies accountable for providing their employees with a safe and inclusive work environment." The Google spokeswoman added that because Google's extended workforce is not composed of employees, those workers are not privy to the same confidential Google company information and can't be a part of groups or attend forums where confidential information is shared or discussed.

Google provides differently colored security badges for employees and TVCs for security and confidentiality purposes, the spokeswoman said. The badges were cited by the TVC letter as an example of "arbitrary and discriminatory separation."

To define the boundaries further, companies like Google may keep contingent workers on one floor of a building, or in some other way separate them from other staff.

HR teams attempting to deal with the workplace issues presented by independent contractors need to be especially careful of the joint-employer element, Absher advised. "Even though you're using a contractor you have some sort of real alternative relationship, you've got to be very cautious about the demands that you draw into those people that work for the contractor because you could find yourself in danger of becoming identified as joint employer."

That's especially true as the conversation in employment trends toward arrangements that are more "agile." Employers are looking to keep up with the pace of innovation by forming teams and workforces that can move from project to project faster. Contingent work is a part of that model, especially in tech, Absher said. But should TVC workers continue to dissent, employers may have to shift course.

"All the things that they're concerned with about not being able to participate as part of the Google family, being part of the population but not part of the Google family … those things could develop that they're going to have to make them employees," Absher said.