This feature is the fifth in a series focused exclusively on issues impacting higher ed IT administrators, running through the beginning of the annual Educause conference, Oct. 25-28. For the series' previous entry, click here.

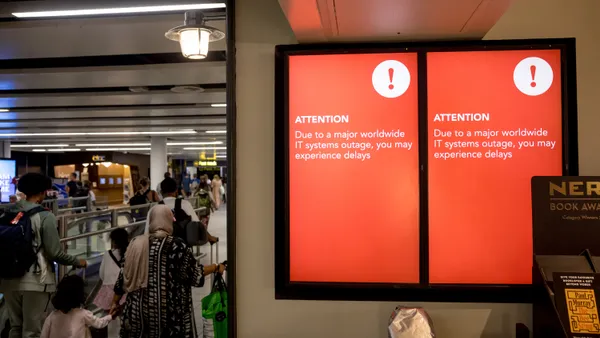

Security has often been an afterthought as technology evolved, and now many sectors are facing cyberthreats that are increasingly difficult to defend against. In higher ed, cybersecurity concerns are ever present as open networks create a broad attack surface, and limited budgets make defense a challenge.

As the threat landscape evolves, there is only so much that campuses can do, but many defense strategies start with awareness, networking, enacting perimeter security and budgeting for the known unknowns organizations may face.

IT security is "really about protecting your data and applications that matter most rather than endpoint devices," said Sasi K. Pillay, vice president for IT services and CIO at Washington State University. "But in the meantime, we're not there yet, so we have to come up with compensating controls."

The more campuses can implement preventative measures to mitigate and remediate security concerns before they become a problem, the better it is from both a cost and business perspective.

Part of the way an organization can improve its security posture is by understanding and properly understanding risk. "We have to understand what our vulnerabilities are of our own systems and services first before somebody finds some before us," Pillay said. Whether it's system upgrades or ensuring patches are put in place, organizations can work to mitigate risk.

On average, it takes higher ed institutions 28 days to patch vulnerable software and applications, according to a 2015 study from SecurityScorecard, which looked at the security posture of 485 higher ed institutions. On top of that, there were large infestations of malware detected, posing a constant threat.

"At the end of the day, some of the things we do probably expose us more than other things we do," Pillay said. But whether it's system upgrades or ensuring patches are put in place, there are many ways for an organization to mitigate risk.

Historic vulnerabilities

"Universities have always been a stomping ground for hackers," said Alex Heid, chief research officer at SecurityScorecard. "Universities were one of the first places that had internet access, and with internet access you have people trying to see how far that can go."

Now, almost every part of university life is online, from applications to registration. But with the rapid implementation of online services, security hasn't always kept pace. "A lot of the colleges use stuff that was written years ago," Heid said. "They'll have a lot of legacy software and hardware that they've implemented haphazardly throughout the years as it's been needed."

Those practices and the security challenges that stem from them are not very unusual across sectors.

"I'm not sure that we're facing anything unique," said Kristen Dietiker, CIO at Menlo College. "The threats out there are just so rapidly evolving that we're just scrambling to keep up."

A part of Menlo's defense strategy is cybersecurity insurance, Dietiker said. Having the insurance can provide insight on a consultant-based fashion, which can help with remediation if anything were to happen. "If we were under attack, they could respond appropriately."

End user behavior

No matter its age, every system usually has at least some security in place. The weak link, more often than not, is the end user. Using an unsecure password or clicking on a suspicious link can have broad ramifications across an organization.

Though students have network access, the biggest risk for security stems from the staff and faculty who have access to institutional and proprietary data. "Now we're talking not just about personal data or security, but also college data," Dietiker said. Once data comes into play, policies and regulations start dictating how that information can be used.

"I'm an old military guy — or I should say I'm a young military guy — and one of the things I've learned is that security is only as strong as its weakest link," said Keith McIntosh, vice president and CIO at the University of Richmond. "You know, we use a chain analogy. It requires everyone who is accessing information on our network — faculty, staff and students — to be security-aware."

At the University of Dayton, Associate Provost and CIO Dr. Thomas Skill estimates he spends about 40% of his time on cybersecurity issues. In January, the university kicked off a proactive, yearlong campaign around "cyber mindfulness," aimed at teaching faculty, students and staff to think of everything they do as a potential security risk.

"We've kind of changed the concept of training there, because most of the training is kind of the old-fashioned, 'Take this online quiz, and then we'll check a box and we know that you've done your cyber training and we know we're secure,'" said Skill. "We realize that nobody remembers a damn thing, so we're doing a whole series of things."

Like other organizations, every month, Dayton's IT department runs phishing tests using a company called KnowBe4, sends updates and warnings and the latest security news, and offers incentives and prizes for people to complete certain actions.

Like many others, Dayton has also rolled out two-factor authentication, but Skill notes that alone still doesn't protect against all threats — including phishing and ransomware — and that a lot of legacy systems aren't compatible with it.

'"We didn't wanna roll out two-factor and have people walk away thinking, 'Oh, security is fixed because we all have two-factor now,'" said Skill. "Our goal here is that this is no different than any athlete training for the toughest competition. Every day, the bad guys out there are coming up with newer, better, smarter, faster ways to trick us into doing stuff, so we've gotta be exercising every day with our effort to understand when we can recognize a phish and when we can't, and we're tracking all the data on what we're doing here."

The efforts have paid off. Skill says he now hears people on campus talking about the phishing test emails or about how the first thing they thought about when they got a new message was whether it was suspicious. "We're not going to be perfect at this," said Skill. "But the fact that people are now talking about it and thinking about cybersecurity as part of their day to day work means that we're being successful."

Looking toward a secure future

For institutions working to implement their own cybersecurity best practices, McIntosh adds that higher ed is lucky to have a number of organizations available to provide support — namely, the Research and Education Network Information Sharing and Analysis Center (REN-ISAC) or the Higher Education Information Security Council (HEISC).

He's also a big fan of National Institute of Standards and Technology's Special Publications 800-53, "Security and Privacy Controls for Federal Information Systems and Organizations."

"It's for the feds," said McIntosh. "But it's a comprehensive security controls assessment that I think we could use and model to help us assess our IT organizations and our infrastructure to make sure we're doing things according to best practices and then implement those within our own institution."

Even with all the recommendations and best practices, making sure a campus stays secure doesn't happen overnight. It's an effort that requires making constant strides to improve IT security posture.

"My vision is I should be able to do very secure computing in a Starbucks. In other words, we have to learn to operate and conduct our business from an environment which is compromised. So that's what we're trying to design toward," Pillay said.

"But in the meantime we've got to put these fixes to kind of shore up what we have. Because many of the applications and the stuff we have deployed does not have security built into it."

Would you like to see more enterprise technology news like this in your inbox on a daily basis? Subscribe to our CIO Dive email newsletter! You may also want to read CIO Dive's look at how higher ed CIOs are working to modernize legacy systems.